Explaining Our Life Expectancy Gap

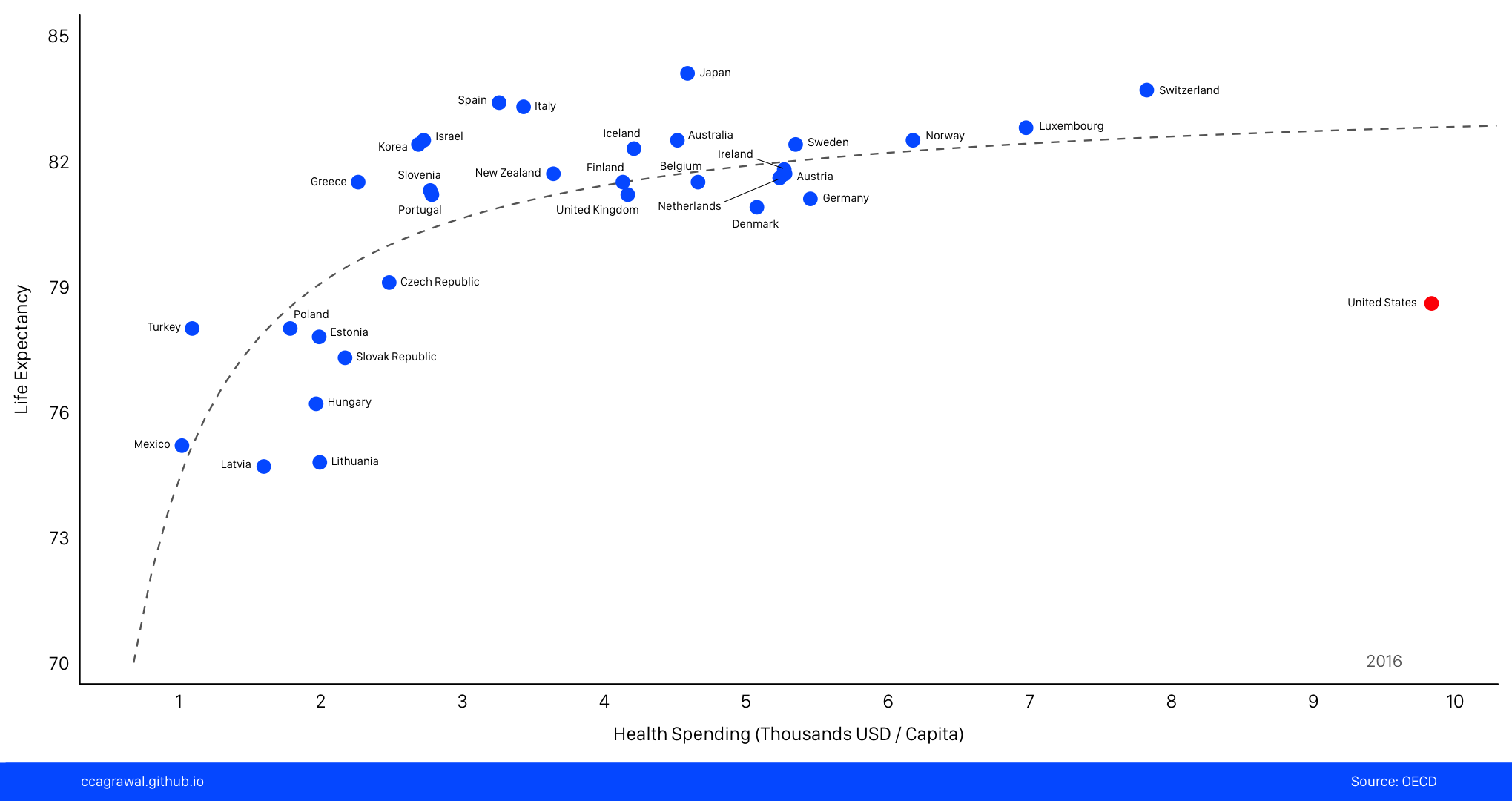

The U.S. spends more on health care than any other OECD nation but ranks among the lowest in life expectancy:

You’ve likely seen some version of this graph before. It’s typically accompanied by a plea for healthcare reform, usually towards a more socialized healthcare system like that of other developed nations. Given our location in the graph above, something must be wrong with our healthcare system.

However, the U.S. is an anomaly in several fashions, many of which lead to early deaths. In this post, I discuss several of these anomalies and argue that our life expectancy shortcoming is the result of confounding variables, rather than a broken healthcare system.

Expected Life Expectancy

The graph above suggests life expectancy should increase with increased spending. But the relationship appears to break down beyond a spending threshold, after which it looks unaffected by changes in spending (aside from the United States).

The animation below shows the same graph from years 2000 to 2016. Wealthy nations (GDP per capita at least 85% of the OECD average) are highlighted. A linear fit of the highlighted nations (excluding the U.S.) is also plotted.

As shown in the animation, the linear fit fluctuates around a horizontal line and doesn’t show a consistent upwards trend. This suggests that among wealthy nations, there isn’t a positive relationship between health spending and life expectancy.

In other words, we shouldn’t expect the U.S. to have the highest life expectancy just because it spends the most. Nevertheless, we should expect the U.S. to have about the same life expectancy that other wealthy nations have.

Confounding Variables

Here are the OECD nations that I use as “comparable” wealthy nations, based on the minimum GDP per capita requirement described above:

- Australia

- Austria

- Belgium

- Denmark

- Finland

- Germany

- Iceland

- Ireland

- Israel

- Italy

- Japan

- Korea

- Luxembourg

- Netherlands

- New Zealand

- Norway

- Spain

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- United Kingdom

Their average life expectancy was 82.2 in 2016. The life expectancy for the U.S. in the same year was 78.6. What explains the 3.6 year gap?

In the next week, I’ll update this post with the confounding variables. I like keeping everybody in suspense.